India

| Attachment | Tamaño |

|---|---|

| English | 914.59 KB |

Organization

Website

Economy on the margins: Risks and exclusion of informal sector e-waste recyclers in policy and practice

Introduction

According to The Global E-waste Monitor, India generates about two million metric tonnes (MT) of e-waste annually and ranks fifth among e-waste producing countries after the United States, China, Japan and Germany.[1] In 2016-2017, India treated only 0.036 MT of e-waste, i.e. 1.8%, as compared to the world average of 20%.[2] Moreover, 95% of India’s e-waste is recycled in the informal sector,[3] characterised by labyrinthine grey market networks. This leads to an increased precarity for the labour force comprising the informal e-waste sector. Since social protection and labour rights already stand eroded for informal sector workers, for informal sector workers in grey markets like e-waste dismantling, both rights and health and safety hazards stand outside reach.

The informal sector also presents significant regulatory challenges in achieving environmental objectives through formalisation. However, policy and regulatory initiatives towards reducing the environmental costs of e-waste generation have failed to recognise the social and economic reality of e-waste in the informal sector. As a result, they have trained their focus on streamlining the processing of waste through formal channels while excluding considerations of the workers whose lives and livelihoods are currently entwined within the existing ecosystem of e-waste processing. For example, national policies like the E-waste (Management) Rules from 2016[4] exclude vulnerable workers with precarious livelihoods, whose exclusion is undercut by the intersectional marginalisation of religion, caste and gender.

This report aims to foreground key considerations about labour rights within the existing debate on e-waste management policy. This is because of the double marginalisation suffered by workers in informal/illegal e-waste dismantling and refurbishment units[5] – firstly, as a result of being a part of the unorganised sector, and secondly, by being a part of an informal sector in the grey market. This is compounded by the unsafe working conditions for precious metal extraction in many of these informal working units, resulting in high occupational health and safety hazards. Further, a large section of the informal labour force is comprised of migrant labour. Migrant labourers do not receive social protection as a result of their migrant status, since they can only benefit from social protection offered by their own state. This results in the complete eclipse of an entire section of the workforce from the development process.

Informality and e-waste policy in India

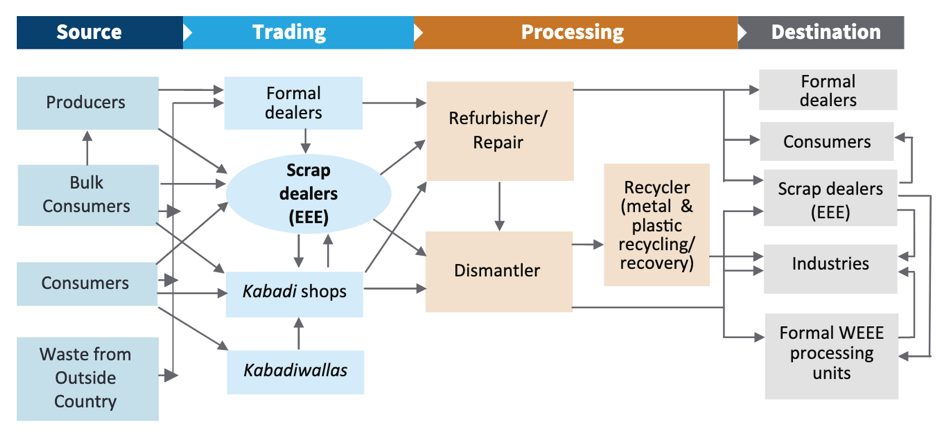

The 2016 E-waste (Management) Rules provided a framework for the formal e-waste ecosystem. It was hoped that this would clean the waste channels and enable the formal ecosystem to take over. Despite these initiatives, the informal sector continues to play the key role in e-waste recycling and management. The informal sector continues to receive e-waste from both informal as well as formal sources like industries. Scrap dealers contribute 38% of the e-waste flowing into the informal sector, while the formal sector, including producers, manufacturers, showrooms, etc., contribute 28% of the e-waste flowing into the sector.[6]

Figure 1. Informal e-waste flow chart

Source: Toxics Link

The architecture of exclusion

The informal sector has been handling 95% of the e-waste being generated in the country.[7] Despite their contributions, the sector and its workers have been neglected by the government in its policies and even by the society which considers the work as dirty and menial. The informal sector has been carrying the burden of e-waste management through its network of waste collectors, segregators, dismantlers and recyclers, which often employs people from marginalised and vulnerable communities such as women,[8] Dalits,[9] and religious minorities.[10] However, in India, the informal sector constitutes 90% of the workforce.[11] Despite the sector’s significant contribution in the labour market and economy, it is not monitored by the government. As a result of remaining outside the government’s regulations, the informal sector is also called a grey labour market.[12]

Informal e-waste workers do not have any legal rights, nor are they adequately covered under social protection schemes such as old age pensions, health insurance, maternity benefits, employee provident funds and gratuity,[13] unlike formal sector workers.[14] The workers in e-waste management even face societal discrimination[15] and regular threats from the law enforcement agencies, as they do not have any identification or any other form of authorisation for working with e‑waste.[16] Moreover, workers handling the e-waste often live near the waste dumping sites; they handle e-waste without any personal protection, exposing themselves to hazardous gases and substances which cause chronic ailments.[17]

The informal e-waste sector is marked by small enterprises, which use unsophisticated technologies with low capital cost. The workers in the sector use hazardous techniques in processing e-waste and extracting precious metals, usually in poorly ventilated workspaces, without having access to health and safety measures, including proper sanitation facilities.[18] While occupational health hazards remain one of the biggest concerns, the lack of social security and affordable access to health care services makes the workers’ situation more precarious. Their working hours are not fixed and their living conditions are deplorable; most of them live in shanties without access to proper and safe drinking water or hygienic sanitation. Their hazardous living and working conditions increase their occupational health and safety risks.

Balancing act: Environment, labour and development

The major issue faced by informal e-waste workers in cities like Seelampur, along with the workers in other e-waste hubs such as Moradabad in Uttar Pradesh or Sai Naka in Mumbai, is that workers are not covered under any social protection schemes. The Unorganised Workers Social Security Act, 2008 (UWSSA),[19] which was supposed to provide welfare schemes to workers on issues related to disability, health and maternity benefits, old age protection and any other benefit required, has failed to reach a population of 458 million working in the informal sector, including e-waste workers.

The act guarantees social protection schemes only to those people falling below the poverty line, instead of providing every worker with basic entitlements. This again leaves a huge proportion of informal workers without a social safety net.[20] The act also remains silent on providing minimum conditions of work such as timely payment of wages, fixed working hours, a fixed minimum wage and special provision for women workers regarding sexual harassment.[21] Despite the contribution of the informal sector to the country’s economic growth, the government spends less than 0.1% of GDP on the social security of these workers.[22] Moreover, there has been a decline in the total spending of the government on the social security of informal workers, from spending 0.09% in 2013-2014 to spending 0.07% in 2017-2018.[23] Because of this, the reason for the failure of the act lies in its drafting as well as inadequate budgetary allocation.

The Social Security Code Bill, 2019[24] aims at universalising all social security schemes. The code will set up a Central Social Security Board and state-level boards, with which the workers will need to register themselves and get an Aadhaar-linked[25] social security account.[26] Other than self-employed workers, all the workers need to establish employer-employee relationships. As per the code, the onus of getting registered rests on the worker rather the contractor, who might not register the workers.[27]

This becomes difficult for home-based workers such as e-waste workers who work with multiple contractors. Identifying employers is difficult, but important, as the contractors have to contribute towards the social security of workers.[28] Secondly, the workers have to make monetary contributions in order to avail social benefits. Those workers falling above the poverty line have to contribute 12.5% to 20% of their wages. Those below the poverty line are exempted, but they will have to periodically submit details of their income and employment.[29]

Working conditions and occupational health

The informal e-waste workers mostly operate from their houses or backyards and from “godowns” (warehouses) where dismantling or recycling units are set up. With home becoming the place of work, the working space is often inadequate. The workers generally live in urban slums; they do not have access to proper ventilation and the lighting is often poor. They also do not have access to proper drinking water or sanitation services. The health problems associated with their work are significant.[30] Despite the plethora of health issues that the workers experience, they remain outside the purview of health-related social protection. The national health insurance scheme Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY), under the Unorganised Workers Social Security Act (UWSSA), 2008, provides inpatient health insurance up to INR 30,000 (USD 408.20) for a five-member family living below the poverty line.[31] However, it has failed to curb the outpatient costs of health care for workers. Instead, the expenditure for both inpatient and outpatient treatment increased by 30% in the year 2016.[32] The health insurance offered to informal workers covers health problems such as those that require surgery or hospitalisation.[33] Waste workers are faced with occupational health conditions such as respiratory illness, skin diseases and cuts and burns which fall under outpatient treatment, and are not covered under the health insurance scheme. This means workers spend a substantial amount of their earnings on health care.[34]

Social protection for women waste workers

The composition of workers involved in e-waste management in the informal sector shows that women form up to 80% of the waste collectors in India. A study conducted by the Centre for Science and Environment to understand the e-waste being generated and dismantled in Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh found that women, especially single mothers, widows and elderly women who are illiterate and do not have any other source of livelihood, are involved in dismantling the e-waste.[35] They work from their houses which fetches them better wages than what they would get by working as a domestic worker.[36]

The UWSSA does not incorporate any specific social protection schemes for women workers in terms of their equal remuneration, as women workers are often discriminated against in wages. They work longer hours, but are paid far less than male workers.[37] As waste workers live near the landfills so that they can get easy access to e-waste, the women are exposed to health hazards such as respiratory problems, birth defects, skin cancers and neurological problems.[38] This further affects their morbidity, mortality and fertility.[39] However, these women workers are not covered by any health and maternity benefits as mandated under the labour laws[40] as they continue to work under dire conditions.

The UWSSA does not even mention safe working conditions for women, such as having proper sanitation services, nor does the act say anything about sexual harassment at the workplace.[41] The Maternity Benefit Act, 1961 provides maternity leave for up to 26 weeks, but it only covers women working in the formal sector and those working in agricultural, commercial or industrial establishments or shops with 10 persons or more, leaving out women working from home such as informal e-waste workers.[42]

Minimum wages and social protection

In India, wages for menial work are fixed by the state government, as per the Minimum Wages Act. The minimum wage for an unskilled worker in Delhi is INR 569[43] (USD 7.59), while the majority of waste workers earn INR 200 per day (USD 2.67) in the city.[44] Although the wages earned in the informal e-waste sector are far less than what is mandated by the government, workers often do not even receive their payments on time,[45] the wage structures are unequal for migrant workers,[46] and women e-waste workers get paid less for equal or even longer working hours.[47]

The informal e-waste sector employs many migrant workers who come to cities looking for livelihood opportunities. These migrant workers do not have any prior skills, and are not protected by legislation. As a result, they are absorbed into the e-waste sector and provide cheap and flexible labour.[48] The migrant workers receive far lower wages compared to local workers.

There is no provision to ensure timely payment of wages in the legislation. The non-payment of wages and delays in payment are the major issues that workers have to constantly face. This also makes it difficult for the waste workers to contribute a certain percentage of their wages as mandated under the Social Security Code Bill to receive the benefit of social protection.

The Pradhan Mantri Shram Yogi Maan-dhan (PM-SYM) scheme is a contributory pension plan for informal workers, including those working in waste management. Under the scheme, the worker receives an amount of INR 3,000 (USD 40.8) per month after their retirement (60 years of age) after paying a premium for 20 years.[49] Workers in the age group of 18-29 would have to contribute INR 55 (USD 0.7) while those above 29 years would have to contribute INR 100 (USD 1.4) per month. However, the scheme is only for workers in the age group of 18-40 years, leaving behind those in the age group of 40-60 years. The monthly contributions can also be difficult for informal waste workers who might not earn enough to pitch in with their contribution.[50]

Conclusion

The existing laws like the Unorganised Workers Social Security Act, 2008 and Social Security Bill, 2019 have failed to recognise the vulnerable condition of waste workers and provide a roadmap for their social and economic upliftment. The e-waste rules have presented a robust framework to channel e-waste in the formal sectors, but have fallen short on recognising the important role played by the informal e-waste economy. Instead, it would rather stop “waste leakages” to the informal sector. Provisions such as extended producer responsibility (EPR) have been introduced, where it is the responsibility of the producer of the electronic or electrical equipment to channel the e-waste to authorised dismantlers and recyclers through take-back systems or setting up collection centres. Collection targets have been set for the producers of the product to collect the electronic and electrical items once they reach their end of life and transfer the e-waste to authorised recyclers and dismantlers.[51]

The process of formalising the informal sector wage workers means obtaining a secure job with worker benefits and social protection. Worker rights include providing for minimum wages, ensuring occupational health and safety measures, providing legal recognition and protection, as well as providing workers with employer contributions in health and pension coverage.[52]

Under the E-waste (Management) Rules, 2016,[53] it is the responsibility of the state labour department to formalise informal waste workers by recognising and registering workers in dismantling and recycling and providing them with training on handling e-waste.[54] However, the explicit process of formalising informal sector workers that is necessary is absent from the rules. Moreover, the process of formalisation is a gradual process and it might not be feasible to suddenly formalise the work lives of all informal workers at once. Instead, there would be certain sections of the informal workforce that would continue to work as they have been.[55]

A study on the informal sector recyclers in Delhi found that post privatisation, 50% of the waste pickers lost their jobs or suffered a decrease in their income. The practice of sharing among waste pickers also reduced, which caused fewer people to earn from the same share of waste. Moreover, due to inflexible working hours, many women were left out, as they were not able to handle both waste picking work and household work.[56]

If the rules are effective in stopping the flow of e-waste to the informal sector, then it would have a direct impact on the livelihood of urban poor who are engaged in collection, trading and recycling of e-waste.[57] Moreover, the informal e-waste sector is both socially and environmentally important; socially by employing people who might not be able to find other work, and environmentally because the manual dismantling of e-waste is important for efficiency in the second-tier formal recycling processes.[58]

There is a need to understand the nuanced role of informal sector waste workers and provide them with the cushion of social security. This would enable not only the better management of e-waste in the country, but would also facilitate the linkages between the formal and informal e-waste economy.

Action steps

The following steps are necessary:

- Better working conditions: The informal sector involved in e-waste management has always been seen as a secondary player and has been excluded from the regulations and major policies.[59] There is a need to lobby for basic social protection for informal e-waste workers, such as fixed working hours, leisure time, ensuring minimum wages and due payment of wages (wages given to informal workers need to be strictly monitored in line with the Minimum Wages Act). There is also a need to provide better working conditions such as safe workspaces and other basic amenities for home-based informal waste workers.[60]

- Ensuring social security benefits for women workers: Women wage workers should be given equal remuneration for their work under the Equal Remuneration Act; the wages should be monitored by forming an employment certification committee that would specifically look into the matter of equal remuneration. The informal workers should be included in the Maternity Benefit Act and the benefits should be linked to wages. Due protection from sexual harassment should be provided to women by forming a complaints committee for wage workers at district and sub-district levels under the Sexual Harassment at the Workplace Act, 2013.[61]

- Ensuring occupational health and safety: E-waste workers are constantly handling hazardous waste and chemicals. The current health insurance programme Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana should also cover outpatient services.[62] This would reduce the medical expenses of workers and will ensure affordability and accessibility of health care services. Contractors should also provide waste workers with adequate tools and safety equipment for handling hazardous substances.[63]

- Universalising social protection: Although the Social Security Code Bill, 2019, talks about universalising social security, it plans to implement it in a contributory way, where both the worker and the government will contribute an amount. This becomes an exclusionary criterion in itself, because many informal wage workers might not have the required amount to be pitched in monthly to access the social security benefit.[64] Instead, all the workers should be provided with social safety nets. Moreover, the Social Security Code Bill requires contractors to register workers, but in case they fail to do so, fines should be levied.[65]

- Recognising the model of privatisation from below: E-waste policies should recognise e-waste as a source of income and wealth, not only for authorised entities. E-waste can also be a means for large-scale poverty alleviation in the cities and would even add to environmental sustainability by allowing the maximum recovery of precious materials that would reduce the dependence on the extractive mining of these materials.[66] At the same time, NGOs can play a role in training informal workers in safety and health measures and risks, and in practising the environmentally sustainable recycling of e-waste.

Footnotes

[1] Baldé, C. P., Forti V., Gray, V., Kuehr, R., & Stegmann, P. (2017). The Global E-waste Monitor 2017: Quantities, Flows and Resources. United Nations University, International Telecommunication Union & International Solid Waste Association. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Climate-Change/Documents/GEM%202017/Global-E-waste%20Monitor%202017%20.pdf

[2] Lahiry, S. (2019, 17 April). Recycling of e-waste in India and its potential. Down To Earth. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/waste/recycling-of-e-waste-in-india-and-its-potential-64034

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change. (2016). E-waste Management Rules, 2016. http://greene.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/EWM-Rules-2016-english-…

[5] Recycling and dismantling workshops.

[6] Mahesh, P. B., & Mukherjee, M. (2019). Informal e-waste recycling in Delhi. Toxics Link. http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/file/Informal%20E-waste.pdf

[7] ASSOCHAM. (2016, 3 June). India’s e-waste growing at 30% per annum: ASSOCHAM-cKinetics study. ASSOCHAM. https://www.assocham.org/newsdetail.php?id=5725

[8] WIEGO, Kagad Kach Patra Kashtakari Panchayat, & Asociación Nacional de Recicladores de Colombia. (2013). Waste Pickers: The Right To Be Recognized As Workers. Position paper presented at the 102nd session of the International Labour Conference, June. https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/WIEGO-Waste-Pickers-Position-Paper.pdf

[9] Dalits are those formerly known as “untouchables” in the Indian caste system. Etymologically the word “Dalit” has its roots in Sanskrit. The root dal (dri) means “to break, crack, to split open and to crush”. In current socio-political discourse, the term is used for people belonging to the Scheduled Castes (the term used for “untouchables” in the Indian constitution).

[10] WIEGO, Kagad Kach Patra Kashtakari Panchayat, & Asociación Nacional de Recicladores de Colombia (2013). Op. cit.; International Labour Organization Sectoral Activities Department & Cooperatives Unit. (2014). Tackling informality in e-waste management: The potential of cooperative enterprises. https://www.ilo.org/sector/Resources/publications/WCMS_315228/lang--en/index.htm

[11] Sharma, S. Y. (2020, 19 January). National database of workers in informal sector in the works. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/indicators/national-database-of-workers-in-informal-sector-in-the-works/articleshow/73394732.cms

[12] Kalyani, M. (2016). Indian informal sector: An analysis. International Journal of Managerial Studies and Research, 4(1), 78-85. https://www.arcjournals.org/pdfs/ijmsr/v4-i1/9.pdf

[13] Gratuity is a term used by the Indian government; it refers to the monetary benefit given by the employer to an employee at the time of retirement under the Payment of Gratuity Act, 1972.

[14] Satpathy, S. (2018). Social Protection to Mitigate Poverty: Examining the Neglect of India's Informal Workers. Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/research/44173-social-protection-to-mitigate-poverty-examining-the-neglect-of-indias-informal-workers; Hoda, A., & Rai, D. K. (2017). Labour Regulations in India: Improving the Social Security Framework. Indian Council for Research in International Economic Relations. https://icrier.org/pdf/Working_Paper_331.pdf

[15] Lines, K., Garside, B., Sinha, S., & Fedorenko, I. (2016). Clean and inclusive? Recycling e-waste in China and India. International Institute for Environment and Development. https://greene.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/IIED-Recycling-E-waste-in-China-and-India.pdf

[16] Kanekal, S. (2019). Challenges in the informal waste sector: Bangalore, India. Penn Institute for Urban Research. https://penniur.upenn.edu/uploads/media/03_Kanekal.pdf

[17] Sinha, S., Mahesh, P., & Dutta, M. (2013). Environment and Livelihood Hand in Hand. Toxics Link. https://toxicslink.org/docs/Environment_and_Livelihoo_d-Hand_in_Hand.pdf; Kanekal, S. (2019). Op. cit.

[18] Sinha, S., Mahesh, P., & Dutta, M. (2013). Op. cit.; Us, V. (2006). Integrating the informal sector into the formal economy: Some policy implications. Sosyoekonomi, 2, 93-112. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273452362_Integrating_the_Informal_Sector_into_the_Formal_Economy_Some_Policy_Implications

[19] https://www.ilo.org/dyn/travail/docs/686/UnorganisedWorkersSocialSecurityAct2008.pdf

[20] Us, V. (2006). Op. cit.

[21] Dutta, T., & Pal, P. (2012). Politics overpowering welfare. Economic & Political Weekly, 47(7), 26-30. https://www.epw.in/journal/2012/07/commentary/politics-overpowering-welfare.html

[22] Singh, J. (2018). A Review of Unorganised Workers’ Social Security Act, 2008. Rajiv Gandhi Institute For Contemporary Studies. https://www.rgics.org/wp-content/uploads/policy-issue-briefs/Issue-Brief-Unorganised-Workers-Social-Security-Act-A-Review.pdf

[23] Ibid.

[24] http://prsindia.org/sites/default/files/bill_files/Code%20on%20Social%2…

[25] Aadhaar is a 12-digit individual identification number issued by the Unique Identification Authority of India on behalf of the Government of India. The number serves as a proof of identity and address, anywhere in India.

[26] Johari, A. (2019, 22 January). Can India’s draft labour code really bring social security to its informal workers? Scroll. https://scroll.in/article/909579/can-indias-draft-labour-code-really-bring-social-security-to-its-informal-workers

[27] Mehrotra, F. (2018, 20 October). Will social security become a reality for home-based workers? The Wire. https://thewire.in/labour/social-security-home-based-workers-labour-code

[28] Ibid.

[29] Johari, A. (2019, 22 January). Op. cit.

[30] Sinha, S., Mahesh, P., & Dutta, M. (2013). Op. cit.

[31] Satpathy, S. (2018). Op. cit.

[32] Karan, A., Yip, W., & Mahal, A. (2017). Extending health insurance to the poor in India: An impact evaluation of Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana on out of pocket spending for healthcare. Social Science & Medicine, 181, 83-92. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5408909/pdf/main.pdf; Hoda, A., & Rai, K. D. (2017). Op. cit.

[33] Satpathy, S. (2018). Op. cit.

[34] Garg, C. C. (2019). Barriers to and Inequities in Coverage and Financing of Health of the Informal Workers in India. Institute for Human Development. http://www.ihdindia.org/Chapter%2019.pdf

[35] Centre for Science and Environment. (2015). Recommendations to address the issues of informal sector involved in e-waste handling: Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh. Centre for Science and Environment. https://cdn.downtoearth.org.in/pdf/moradabad%20-e-waste.pdf

[36] International Labour Office Sectoral Policies Department. (2019). From waste to jobs: Decent work challenges and opportunities in the management of e-waste in India. International Labour Organization. https://www.ilo.org/sector/Resources/publications/WCMS_732426/lang--en/index.htm

[37] Goswami, P. (2009). A critique of the unorganised workers’ social security act. Economic & Political Weekly, 44(11), 17-18. https://www.epw.in/journal/2009/11/commentary/critique-unorganised-workers-social-security-act.html

[38] Ganguly, R. (2016). E-waste Management in India – An Overview. International Journal of Earth Sciences and Engineering, 9(2), 574-588. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305268040_E-waste_Management_in_India_-_An_Overview

[39] McAllister, L., Magee, A., & Hale, B. (2014). Women, E-waste, and Technological Solutions to Climate Change. Health and Human Rights Journal, 16(1), 166-178. https://cdn2.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2014/06/McAllister1.pdf

[40] International Labour Office Sectoral Policies Department. (2019). Op. cit.

[41] Goswami, P. (2009). Op. cit.

[42] Rao, M. (2016, 13 August). Maternity leave increases to 26 weeks – but only for a small section of Indian women. Scroll. https://scroll.in/pulse/813888/maternity-leave-increases-to-26-weeks-but-only-for-a-small-section-of-indian-women

[43] https://labour.delhi.gov.in/sites/default/files/All-PDF/Order_MW2019.pdf

[44] Bhaduri, A. (2018, 17 April). Down in the Dumps: The Tale of Delhi's Waste Pickers. The Wire. https://thewire.in/health/down-in-the-dumps-the-tale-of-delhis-waste-pickers

[45] Goswami, P. (2009). Op. cit.

[46] Sinha, S., Mahesh, P., & Dutta, M. (2013). Op. cit.

[47] Ibid.

[48] National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector. (2007). Report on Conditions of Work and Promotion of Livelihoods in the Unorganised Sector. https://dcmsme.gov.in/Condition_of_workers_sep_2007.pdf

[49] Ratho, A. (2019, 30 October). Will new social security schemes provide relief to the informal sector? Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/will-new-social-security-schemes-provide-relief-informal-sector-57105

[50] Sane, R. (2019, 14 March). Two pension schemes, one problem: What Modi govt didn’t learn. The Print. https://theprint.in/opinion/two-pension-schemes-one-problem-what-modi-govt-didnt-learn/205018

[51] Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change. (2016). Op. cit.

[52] Chen, M. A. (2012). The Informal Economy: Definitions, Theories and Policies. WIEGO. https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/Chen_WIEGO_WP1.pdf

[53] Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change. (2016). Op. cit.

[54] Ganesan, R. (2016, 23 March). New E-waste rules announced. Down To Earth. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/waste/new-e-waste-rules-announced-welcome-change-from-the-previous-set-53289

[55] Chen, M. A. (2012). Op. cit.

[56] Chaturvedi, B., & Gidwani, V. (2010). The right to waste: Informal sector recyclers and struggles for social justice in post-reform urban India. In W. Ahmed, A. Kundu, & R. Peet (Eds.), India’s New Economic Policy: A critical analysis. Routledge. https://www.academia.edu/30124057/The_Right_To_Waste_Informal_Sector_Recyclers_and_Struggles_for_Social_Justice_in_Post-Reform_India_2010_

[57] Lines, K., Garside, B., Sinha, S., & Fedorenko, I. (2016). Op. cit.

[58] Sinha, S., Mahesh, P., & Dutta, M. (2013). Op. cit.

[59] Turaga, R. M. R., Bhaskar, K., et al. (2019). E-waste Management in India: Issues and Strategies. Vikalpa, 44(3), 127-162. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0256090919880655

[60] National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector. (2007). Op. cit.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Karan, A. (2017, 11 October). India’s flagship health insurance scheme for the poor has failed to cut medical expenses. Here’s why. Scroll. https://scroll.in/pulse/853652/indias-flagship-health-insurance-scheme-for-the-poor-has-failed-to-cut-medical-expenses-heres-why

[63] National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector. (2007). Op. cit.

[64] Johari, A. (2019, 22 January). Op. cit.

[65] Mehrotra, F. (2018, 20 October). Op. cit.

[66] Turaga, R. M. R., Bhaskar, K., et al. (2019). Op.cit.; Chaturvedi, B., & Gidwani, V. (2010). Op. cit.

Notes:

This report was originally published as part of a larger compilation: “Global Information Society Watch 2020: Technology, the environment and a sustainable world: Responses from the global South"

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) - Some rights reserved.

ISBN 978-92-95113-40-4

APC Serial: APC-202104-CIPP-R-EN-DIGITAL-330

ISBN 978-92-95113-41-1

APC Serial: APC-202104-CIPP-R-EN-P-331