The online terrain for women’s rights

| Attachment | Veličina |

|---|---|

| Introduction.pdf | 668.13 KB |

Organization

Website

I remember vividly the day, in 2003, that the name of the United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) was stolen online by a pornographer. I was the deputy director of UNIFEM and the head of our communications division came running into my office, frantic, and told me to search online for “www.unifem.com”. Pornographic images filled my screen and it created a loop that took many tense moments to close.

I remember the feelings of violation and horror. And, as we tried, largely with futility, to find out if we had any rights to reclaim our identity, I recall our frustration and helplessness. It didn’t matter that this had also happened to UNICEF. It didn’t matter that unifem.com was not our main website, but a URL that we bought precisely to avoid it being used by others, nor that our frustrated web manager was unable to get a bureaucratic administration to pay the USD 65 needed to renew it on time, resulting in an alleged Russian pornographic enterprise scooping it up within several hours of our URL elapsing. I shuddered at the thought that innocent internet users would put “UNIFEM” in the subject line on their search engine, and might very likely get trapped in the same loop of degrading images of women that I did. The deliberate efforts of a pornographer to capture a URL of a women’s rights organisation made it more insidious.

After nearly four months of consulting with UN lawyers, US and Russian officials, and internet legal specialists – and following disturbing phone calls and emails from the entity or individual that had “captured” our URL and was now offering to sell it to us for USD 1,500 – we had no resolution. This was uncharted territory and, as many experts told us, legal regimes and remedies did not keep pace with the types of violations that were occurring. There was no agency that had clear jurisdiction to intervene in this situation; it was a perpetrator-free crime.

Our dilemma ended because of serendipity. An anonymous donor bought the URL and donated it to us, paying USD 400 into an account in Russia. We learned, of course, to never let bureaucracy interfere with expeditious renewals of our URLs. But something changed forever: we braced ourselves for the next attack. Given the pace of technological innovation and the profitability and impunity for perpetrators, there was a feeling of inevitability about it.

Many individuals and organisations working at the intersection of feminism, social justice, human rights, and information technology echo the observations in a recent report: “If we agree that the online world is socially constructed, then gender norms, stereotypes and inequality that exist offline… can be replicated online.” [1] This is not necessarily at the forefront of thinking when one’s business is expanding because of online sales, when telemedicine brings powerful diagnostic tools to rural areas to save lives, or when online activism helps to unite the opposition and bring down a dictator, as we saw in the Egyptian and Tunisian uprisings in 2011. But as we laud the power of the internet to inform, break through isolation, and unite, we must also recognise its power to misinform, divide and put individual and collective rights in direct conflict with one another.

That is why this issue of GISWatch is so important and why I was so pleased to be asked to contribute. During nearly 40 years of work as a women’s rights advocate and nearly 15 years of working in the UN – with a strong belief in the power of linking normative global policy to local-level organising and change – I have been privileged to witness, time and time again, how the collective voice and strategies of women’s rights advocates change opportunities and agendas on issues of major importance to human security and survival. The premise of this article is that the local and global discussions and renegotiation of policy priorities that are taking place – as part of the World Summit on the Information Society review (WSIS+10), the 20-year review of the UN Fourth World Conference on Women and its Beijing Platform for Action, and the post-2015 development agenda[2] – represent an opportunity for women’s rights constituencies to reframe and reposition the ways that the internet and other information and communications technologies (ICTs) can be deployed to advance, rather than reverse, progress on women’s rights. This is a unique opportunity to generate innovative and aspirational ideas for legal and policy changes that more effectively harness the power of the internet to expand gender equality. This introduction proposes a “lens” for better understanding and reframing gender regimes on the internet, and calls for expanding constituencies for human rights and women’s rights in discussions on ICTs as an urgent priority.

Mapping gender regimes in the online world

ICTs, alone, cannot change inequitable systems and values. But we already have evidence that the radical potential of the internet to be a positive force for change in women’s and girls’ access to their human rights and for social justice is undeniable. One of many examples is the Women’s Learning Partnership, which has a programme that supports women’s rights advocates to harness the power of information technologies. It describes the internet’s huge potential:

Women's rights activists [in Iran] have used every communication technology tool at their disposal to create a grassroots campaign demanding an end to discriminatory laws. Their website is attacked. They move to another domain. Activists are imprisoned. They release urgent alerts bringing it to the world's attention almost instantaneously. And, with all of these tools, they are successful. The Iranian government recently withdrew a draconian family protection bill that would have further circumscribed women's freedoms. Iranian women face many mighty foes in their centuries-old struggle for gender equality. Given what technology now makes possible, they now have a mightier friend. And therein lies a lesson and an inspiration for all of us who wish to foster democracy and social change.[3]

At the same time, the ways that this “mightier friend” can reinforce existing inequalities and create new ones emerge almost daily. Unlike legal remedies, which are slow to keep pace, the fast-growing lexicon – from “cyber stalking” [4] to “sexting”[5] – is evidence of a rapidly expanding array of new threats to women’s rights. Research by the Association for Progressive Communications (APC)[6] revealed many examples: in Cambodia, for instance, it is very common for men to violate their female partners' privacy rights through tracking and controlling, using GPS and spyware devices.

While the online world often replicates and potentially exacerbates the offline world’s existing opportunities and inequalities – including those related to gender, class, race, disability and other lines of identity – it also requires us to adjust the lens of gender and human rights that we apply offline to enable us to map and claim our rights in this new terrain. Many strategies from “offline” power struggles are applicable, but the online terrain is far from a mirror image. Mapping the gender regimes that exist in this terrain is essential to the task of envisioning what the internet would look like with greater gender equality and women’s rights.

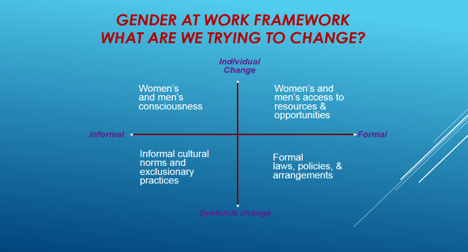

This article applies the Gender at Work framework to generate a broader view of some of the options, opportunities and challenges for advancing and protecting women’s human rights online. This is an incipient analysis. Bringing more experiences, more contexts and more perspective into this analysis could generate a much more complex and relevant change strategy and help us to articulate concrete policy demands that, at once, take into account the interlinked changes needed at the national, regional and global level.

The Gender at Work framework

The four-quadrant framework, based on Ken Wilber’s Integral Model, enables a quick assessment of where change that affects gender equality is happening or needs to happen in institutions and organisations.[7] It distinguishes two polarities: (1) individual and systemic change, and (2) formal (visible) and informal (hidden) experience. Many proposed solutions to gender inequality focus on only one quadrant, or perhaps two. Gender at Work’s hypothesis is that change will be more comprehensive and sustainable when efforts focus on all four quadrants.

Starting in the upper right-hand side of the framework: What resources are needed to promote and protect women’s rights on the internet?

The two quadrants on the right-hand side of the matrix relate to what is visible and therefore “trackable” in terms of change. Starting on the upper right-hand side of the quadrant brings us to the question of how formal and visible resource distribution generated by the internet impacts on gender equality.

Much of the discussion about the internet has focused on its potential to generate resources related to income, time, anonymity, global solidarity and other benefits to both women and men. This could have particular application, for instance, to women who have restricted mobility, whether because of their rural location, disability, or religious/cultural practices.

The Institute for the Future identifies six drivers most likely to shape the future workforce: longer life spans; a rise in smart devices and systems; advances in computational systems such as sensors and processing power; new multimedia technology; the continuing evolution of social media; and a globally connected world. The ICT sector clearly underpins an important segment of the future of work and livelihoods. Women are not well-positioned in this future. An International Telecommunication Union (ITU) report cited that in February 2009, for example, women accounted for only 25% of all IT occupations, the exact same proportion of IT occupations held by women in March 2000. Without a better understanding of the gendered digital divide, a number of trends suggest that those who are most excluded will be further marginalised in this environment.[8]

At the same time, recent expert group meetings in preparation for WSIS+10 have affirmed that there is inadequate data to assess the different facets of the gender digital divide, especially in developing countries. Evidence to date shows inequalities in many dimensions, with the gender divide varying by region, country and within countries, and dependent on education and incomes. The first divide – that 77% of people in developed countries are online against only 31% of people in developing ones – has a riveting effect on reaching the most excluded.[9] And while recent data notes that 46% of the global web population is female, this masks other disparities. In wealthier regions such as in North America, the web population is evenly split. A UN Women/US State Department/Intel report cites that, on average across the developing world, nearly 25% fewer women than men have access to the internet, and the gender gap soars to nearly 45% in regions such as sub-Saharan Africa. This is despite anticipated benefits nationally and globally. The same report estimates that facilitating an additional 600 million women to get online would mean that 40% of women and girls in developing countries, nearly double the share today, would have access to the transformative power of the internet and potentially contribute an estimated USD 13 billion to USD 18 billion to annual GDP across 144 developing countries. [10]

Even without comprehensive gender-disaggregated data,[11] there are many emerging initiatives that have shown the ways in which the internet and connectivity in general can create new types of illiteracies which emanate directly from divides of gender, race, location and class. As studies on gender and ICTs in Africa highlighted, women’s access to connectivity and use of the internet are mediated by education, financial means, time, safety and security of location, technophobia and the fact that there is often inadequate content for women and girls. One Moroccan woman interviewed for an International Development Research Centre (IDRC) study commented, “[The internet] has become a necessity and the one who does not know how to use it is illiterate. I consider myself illiterate. I started learning for some time, then I gave up. One needs many hours per day.”[12]

And while the priority needs to be on ensuring that women and girls who are most disadvantaged have equal access to the resources and opportunities that the internet generates, complex dynamics resulting from gendered resource constraints in the larger society influence use and access to the internet even in the richest countries. While addressing a group of large companies in Spain that had signed on to the Women’s Empowerment Principles as part of their corporate social responsibility programmes, [13] a number of younger women from a large, national supermarket chain explained to me how an internal personnel survey had revealed that women’s stress levels and career opportunities were adversely impacted by use of email and electronic communities of practice by employees over the weekend. The survey had assessed that men found it easier to participate because they had fewer domestic responsibilities at home: their careers benefitted from their ability to continue to work online over the weekend, to respond to emails quickly and from the absence of the added stress that women experienced. The company responded by prohibiting email traffic during the weekends, a policy that generated an immediate effect on levelling the playing field. This company is an exception in recognising inequalities that emerge due to domestic time pressures. The gendered division of labour that continues worldwide will continue to have unique manifestations on the internet in all contexts.

Moving to the lower right-hand side of the framework: What policies are needed to promote and protect women’s rights on the internet?

The question of policy formulation at all levels – global, regional, national and local – to promote and protect women’s rights on the internet is particularly relevant at this moment, given the local and global convenings related to WSIS+10, the post-2015 development agenda, and the 20-year review of the Beijing Platform for Action. As others have noted, some international organisations and civil society groups are already engaging with issues that concern the democratisation of the ICT arena, from the digital divide and the right to communicate, to cultural diversity and intellectual property rights. Gender equality advocates have also been in alliance with broader networks in pushing to address the gender dimensions of the information society: integrating gender perspectives in national ICT policies and strategies, providing content relevant to women, promoting women’s economic participation in the information economy, and addressing violence against women and children on the internet. [14] A key example of this is the Women, ICT and Development (WICTAD) Coalition, made up of a range of stakeholders that seek to share learning, identify opportunities for collaboration and alignment, highlight and make efforts to fill gaps in understanding and investment, produce recommended actions for the post-2015 UN development agenda, as well as generate a new consensus on the importance of leveraging ICTs for women in development agendas. The coalition, comprising a number of workstreams led by different organisations, covers access to ICTs, digital literacy, health, education, political participation, entrepreneurship, content producers, ICT careers, ICT policies, and data and research.

These alliances have already generated precedents to build on. At the first WSIS (2003), member states agreed that the “development of ICTs provides enormous opportunities for women, who should be an integral part of, and key actors in, the Information Society. We are committed to ensuring that the Information Society enables women’s empowerment and… full participation on the basis of equality in all spheres of society and in all decision-making processes. … [W]e should mainstream a gender equality perspective and use ICTs as a tool to that end.”[15]

Amplifying the collective voice of women’s movements from different countries and contexts in relation to WSIS+10 and its relevance to overall ICT policy is a strategy that requires support. We should learn from the experience in 2003 – where there were two coalitions advocating for women’s rights, sometimes at cross purposes and, in general, insufficient engagement by feminists with WSIS overall – to enable us to secure a policy agenda that can be carried through the Beijing and post-2015 debates. There are a wide range of policy options to advocate for, from securing national commitments to disaggregate data by gender on ICT use and access, to introducing quotas or positive action for participation of women and girls as participants and decision makers in ICT education and governance, or introducing subsidies that make ICTs affordable for rural communities and, particularly, for women and girls who have restricted access. But we have to continue to press and build a case for concrete and targeted commitments, rather than the kinds of vague statements that are so easily eluded in practice.

The terrain that remains in dire need of feminist framing and activism is the policy void and resistance to address the multiple ways that the internet has become a prime site of sexual exploitation and abuse. As Fascendini and Fialová note:

The complex relationship between violence against women (VAW) and information and communications technologies (ICTs) is a critical area of engagement for women's rights activists. ICTs can be used as a tool to stop VAW, while on the other hand VAW can be facilitated through the use of ICTs. However, few women's rights activists are working actively on this issue. Consequently, a political and legal framing of the issue is not established in most countries. [16]

Globally agreed norms and standards can help to inspire countries to incorporate these in their domestic frameworks.

In 2013 the UN Commission on the Status of Women committed member states to:

Support the development and use of ICT and social media as a resource for the empowerment of women and girls, including access to information on the prevention of and response to violence against women and girls; and develop mechanisms to combat the use of ICT and social media to perpetrate violence against women and girls, including the criminal misuse of ICT for sexual harassment, sexual exploitation, child pornography and trafficking. [17]

This resolution, and several others, are important policy steps that activists can use at national level to press for changes in national ICT and security policies and anti-violence legislation. But we have to go further.

Firstly, laws and policies to protect women and girls from violence need to be reframed to recognise, prevent and redress new forms of technology-related VAW. This means taking such steps as expanding definitions of violence and harm beyond physical harms [18] and introducing laws that deal with new phenomena like cyber stalking, “sextortion” and other online violations. We need laws, policies and standards that are aimed at prevention and that are accompanied by education programmes for women and girls on how to negotiate online spaces and sexual interactions safely.

Secondly, radically new approaches to privacy laws will be critical. This is complex terrain that requires deep feminist thought and advocacy. The experience from Malaysia (see Box 1) is an example of how violations of women’s privacy rights have reverberating effects on individuals and societies.

|

Box 1: In February 2009, intimate pictures of a Malaysian female politician were sent, allegedly by her partner, to local daily newspapers and subsequently posted online and circulated via mobile phones. While newspapers did not publish the pictures, they questioned and reportedly bullied the politician over the images. Her political opponents used the leaked photos and videos to question her morality and demand her resignation. Despite her public statement that she did not feel embarrassed or compromised, she resigned from her political post. Due to overwhelming public support, her resignation was eventually rejected by the government. Although the Constitution of Malaysia enshrines a conclusive list of fundamental rights, including freedom of assembly, speech and movement, it does not specifically recognise the right to privacy.[19] |

Thirdly, the need to balance one person's right to privacy with another person's right to know – two basic human rights – makes this a particularly complex policy terrain. Often the way that these rights are defined depends on power relations within a society. This debate has traditionally generated significant friction within feminist and social justice movements, unmasking divisions of race, class and other perspectives between those who advocate for limits to freedom of expression that are needed to strike a balance with other human rights and those who believe that freedom of expression must be absolute.

The complexity of this terrain was uniquely visible in May 2013, when a coalition led a week-long campaign to hold Facebook accountable for its policy on dealing with hate speech and the representations of gender-based violence shared by its users. Within one week, the Everyday Sexism Project, Women Action & the Media (WAM!) and activist and writer Soraya Chemaly succeeded in generating enough pressure on Facebook to get the USD 1.4-billion company to admit that content on the site has been “evaluated using outdated criteria” and to promise to review and update their Community Standards around hate speech. In response, freedom of expression advocates have voiced concern and criticism over the precedent set by demands for Facebook to remove hateful content from its site.

Despite this ongoing debate, there is clear space for agreement on the need for accountability in how internet intermediaries deal with abusive content, a point made by advocates from a variety of backgrounds, including the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression.[20] If human rights are indivisible, inalienable and interdependent, then freedom of expression cannot trump the right to live a life free of violence. Collective advocacy to move this agenda over the next three years of global policy debates could be an important contribution of women’s and social justice movements to creating an online environment that respects freedom of expression and individual rights to safety.

Moving to the left-hand side of the framework: What changes in individual consciousness and invisible norms and cultures are needed?

Securing resources and policies that create opportunities for more women and girls to access and use the internet – or for more women’s rights advocates to have an equal voice in decision making about internet governance – will fall short unless ample attention is paid to the left-hand side of the Gender at Work framework: that is, the largely invisible and expensive-to-track areas of individual attitudes and collective norms and values that ultimately influence our choices, our attitudes and our actions.

There are two dimensions to monitoring and changing individual attitudes that perpetuate gender discrimination on the internet (the upper left-hand quadrant). Firstly, there is the power of the internet to track and change the attitudes of those who actively promote or enable gender discrimination, both online and offline; secondly, there are the attitudes of women themselves, who can encounter both empowerment and disempowerment within the power of the internet.

The ways that the internet increases reach, with the ability to build robust and rapidly expanded social networks across vast geographic divides and to reach millions in cyberspace with the click of a button – from emails to Twitter and Facebook – mean that empowerment or abuse can happen every moment of every day, all year long. The power of campaigns like the Bell Bajao and One Million Men/One Million Promises run by Breakthrough[21] – using a combination of new and traditional ICTs, including the internet, television and community-based training in order to amplify positive messages and build communities around men’s responsibility to stand up to end violence against women – is a positive example of using existing online and offline capacity and inspiring others to do so.

At the same time, this is the terrain where online and offline strategies are mutually reinforcing. The use of patriarchal power to restrict or intimidate women’s and girls’ use of and influence on new technologies emanates from cultures and attitudes about masculinity. A study in West Africa affirmed what has been proven in other regions: many men felt threatened when women used mobile phones and accessed the internet, seeing it as destabilising to relationships and inappropriate. Many cases were reported of men monitoring the mobile phone and internet use of their partners. A woman from Cameroon commented, “My husband won’t let me have a cellphone; I have asked him several times to get me one. He answers that if I want a divorce, I just have to say so.”[22]

Or, as a Moroccan woman observed, “In internet cafés, men are not supervised. They sometimes use pornographic websites… and nobody cares about that. But the women feel embarrassed because we are watched by others who keep an eye on what we are writing or watching, even by the internet café’s owner. There is no privacy.”[23]

Despite intimidation, women are persevering and showing great courage to use the internet to break cycles of silence, draw attention to women’s human rights abuses, form new kinds of social networks, and infiltrate male-dominated spheres, whether as hackers or bloggers. Women’s rights advocates are using the internet to draw attention to rape, abductions and many other human rights abuses, often at great risk to themselves. As one woman blogger from Mexico noted, “When women bloggers… manage to get their voices heard, that is when they start receiving the most pressure, threats and smear campaigns. …This happens to all of us, whether we are in Tunisia, Ciudad Juárez [Mexico] or Saudi Arabia… because when power feels it is under attack, it reacts against the voices that provoke debate.”[24]

Reversing individual and collective attitudes that restrict women’s full participation in the benefits of the internet and that perpetuate patriarchal control and abuse is the ongoing work of women’s and social change movements. This work must be focused on democratising cyberspace as well. As in other spheres, from politics to the larger terrain of science and technology, one aspect of changing patriarchal norms and standards is to strive for greater gender balance amongst experts and decision makers in particular fields. This remains an important strategy in relation to the internet. Positive images of women who are leaders and technological wizards in the tech field are the exception, but exist nevertheless. A media report from Zambia[25] illustrates the ways in which some women in the tech field understand their importance as role models and “norms breakers”. At a Women’s Rights Brainstorm and Hackathon in Zambia in March 2013, Clara Malupande, an ICT specialist who spoke about her experience in the ICT field, noted, “I love being able to challenge social norms and do things that people least expect me to be capable of.” An often-asked question she receives is: “Can you cook?” The Zambian article noted that this question highlights the perception that women in male-dominated sectors are unable to perform what are deemed to be “traditional” duties, a belief exhibited in countries worldwide.

What changes in informal cultural norms and practices are needed?

Finally, the lower left-hand quadrant of the Gender at Work framework focuses on informal cultural norms and exclusionary practices. It is here that we see how existing power relations in society determine the enjoyment of benefits from ICTs. It is here where collective and well-entrenched cultural, gender, class and race biases determine who benefits and who controls cyberspace, regardless of which formal policies are in place. As Gurumurthy observes, at its highest levels, the ICT arena is characterised by strategic control exercised by powerful corporations and nations, reliant on monopolies built upon the intellectual property regime, increasing surveillance of the internet, and exploitation by capitalist imperialism, sexism and racism.[26] Building a policy-to-action cycle that embraces all of the quadrants and is mindful of the cultural and traditional norms that mediate the internet is an important new terrain for challenging patriarchy and privilege by asserting claims for women’s rights and the rights of all groups that are excluded from the benefits of development.

Conclusion

Strengthening capacity to use and govern the internet for advancing human rights and weakening its potential to exacerbate inequality and abuse will require what women’s movements have long brought to other complex phenomena: the power of feminist analysis and reframing concepts so that they can be transformed into policies; the power of information dissemination and awareness raising to build constituencies; the power of collective voice and organising to face down injustice and exploitation and to model new types of interactions and relationships.

In a 2011 article for the Association for Women's Rights in Development (AWID),[27] Jenny Radloff rightly urged that “we need to take control of [information] technologies, deploy them creatively and infuse our technology practice with feminist principles in order to enhance and deepen our movement building.” At the same time, we need to inspire women’s movements to challenge gender-discriminatory policies and practices that characterise the internet and ensure that the radical potential of this terrain to promote and protect women’s rights can be enjoyed by all.

References

[1] Fascendini, F. and Fialová, K. (2011) Voices from Digital Spaces: Technology-related violence against women, Women’s Networking Support Programme of the Association for Progressive Communications. www.apc.org/en/pubs/voices-digital-spaces-technology-related-violence-0

[2] These are all United Nations processes, most of which involve consultations at local, regional and global levels and will culminate in 2015. Ultimately, these processes will lead to some type of outcome document or resolution that the 193 member states of the United Nations will agree to and then will be accountable for implementing. For more information on each, see: www.itu.int/wsis/index.html (for the WSIS+10 review, which is led by the International Telecommunication Union), www.un.org/womenwatch (for the Beijing+20 review, which will be led by UN Women) and www.un.org/en/development/desa/development-beyond-2015.html (for the process that will determine the post-2015 development agenda, the successor to the Millennium Development Goals).

[3] Interview with Ms. Usha Venkatachallam, director of Innovation and Technology at WLP on the World Movement for Democracy. See: www.wmd.org/resources/whats-being-done/information-and-communication-te…’s-learning-par

[4] Cyber stalking includes (repeatedly) sending threats or false accusations via email or mobile phone, making threatening or false posts on websites, stealing a person's identity or data, and spying on and monitoring a person's computer and internet use.

[5] Sexting is a form of “texting” that involves the creating, sharing and forwarding of sexually suggestive images or messages, primarily between mobile phones

[6] Fascendi and Fialová (2011) Op. cit.

[7] For more information on the Gender at Work analysis and support to organisational change initiatives, please visit www.genderatwork.org

[8] Tandon, N. (2012) A Bright Future in ICTs Opportunities for New Generation of Women, ITU, Geneva.

[9] en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_Internet_usage

[10] newsroom.intel.com/community/intel_newsroom/blog/2013/01/10/intel-announces-groundbreaking-women-and-the-web-report-with-un-women-and-state-department

[11] Initiatives like the Partnership on Measuring ICT for Development (www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/intlcoop/partnership/default.aspx) can help build the capacity of developing countries to collect and disseminate official sex-disaggregated and gender-related ICT statistics.

[12] Buskens, I. and Webb, A. (2009) African Women and ICTs: Investigating Technology, Gender and Empowerment, Zed/IDRC.

[13] www.unglobalcompact.org/Issues/human_rights/equality_means_business.htm…

[14] Gurumurthy, A. (2004) Gender and ICTs: Overview Report, Bridge, Brighton.

[15] www.itu.int/wsis/docs/geneva/official/dop.html

[16] Fascendini and Fialová (2011) Op. cit.

[17] www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/csw/csw57/CSW57_agreed_conclusions_advance_un…

[18] Fascendini and Fialová (2011) Op. cit.

[19] Ibid.

[20] www.takebackthetech.net/blog-feeds/44

[21] breakthrough.tv/explore/campaign/ring-the-bell

[22] Hafkin, N. and Huyer, S. (2006) Cinderella or Cyberella: Empowering Women in the Knowledge Society, Kumarian Press.

[23] Buskens and Webb (2009) Op. cit.

[24] www.ipsnews.net/2012/10/women-using-icts-to-change-the-world

[25] www.zedtechnologynews.com/?p=372#sthash.a6eolOHF.dpuf

[26] Gurumurthy (2004) Op. cit.

[27] www.awid.org/News-Analysis/Friday-Files/ICTs-A-double-edged-sword-for-W…